Movement Disorders

- related: Neurology

- tags: #neurology

Overview of Movement Disorders

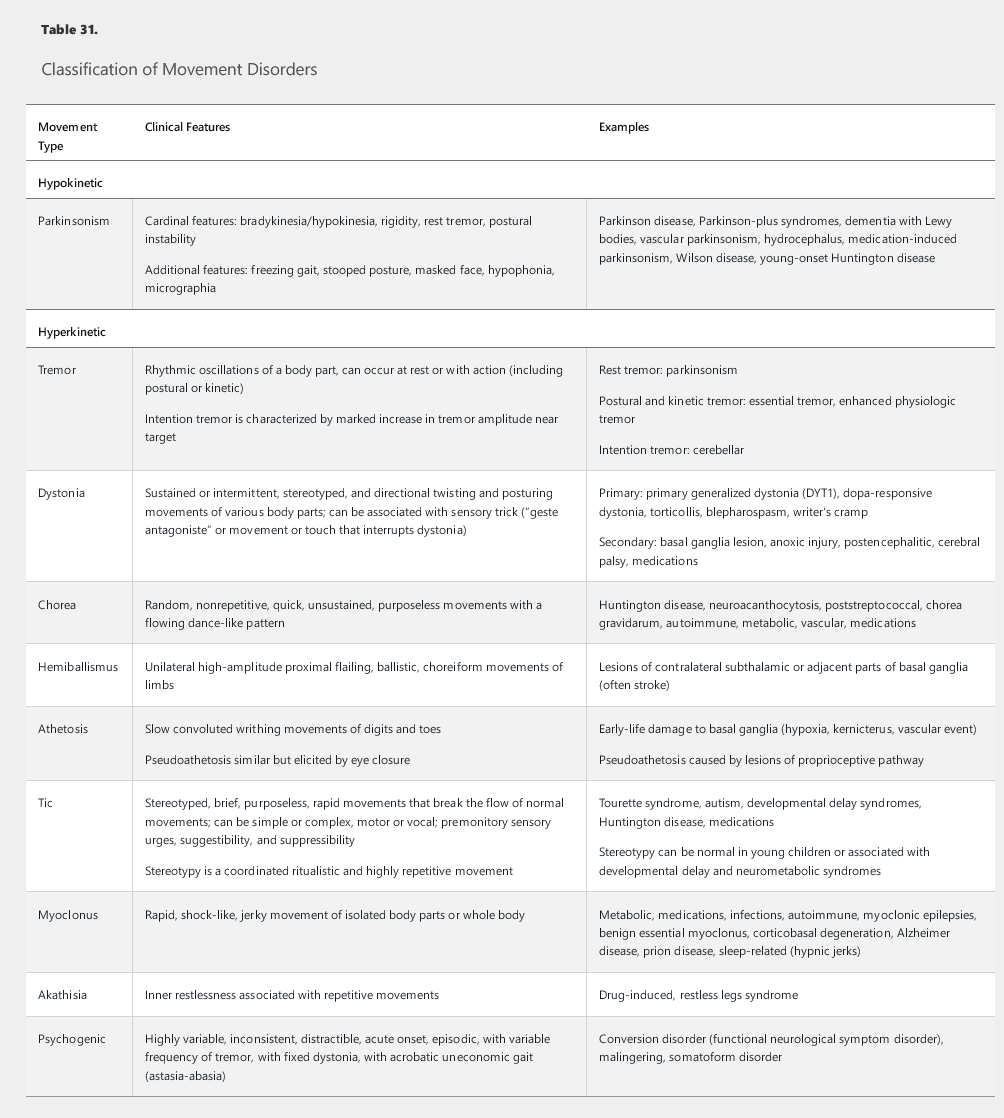

Movement disorders are characterized by hypokinetic and hyperkinetic patterns of motor output. The most typical hypokinetic pattern, parkinsonism, is characterized by paucity and slowness of movements. Hyperkinetic disorders are categorized on the basis of the type of involuntary excessive movements displayed (Table 31).

Neurologic examination of movement disorders should include detailed assessment of motor function and gait. The key features in the classification of movement disorders are the speed, amplitude, and fatigability of voluntary movements and the rhythmicity, suppressibility, randomness, and directionality of hyperkinetic movements. Muscle tone should be assessed for rigidity, which is an increase in resistance to passive movements that is independent of the velocity and direction of those movements. Gait examination should consider the base of standing, pace of ambulation, stride length, foot clearance off the ground, postural stability, and arm swing.

Hypokinetic Movement Disorders

The most common type of hypokinetic movement disorder is parkinsonism. Parkinson disease is the most common form of parkinsonism; Parkinson-plus syndromes combine features of parkinsonism with other features found in the patient's history or physical examination. Vascular parkinsonism results from microvascular disease or large strokes and is characterized by predominant gait impairment with relative sparing of upper extremities. Parkinsonism also may arise as an adverse effect of medication. Some patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus exhibit parkinsonism with gait instability, dementia, and urinary incontinence (see Cognitive Impairment).

Parkinson Disease

Parkinson disease is a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disorder involving the gradual loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra. Pathologic findings include the aggregation of α-synuclein protein and formation of Lewy body inclusions in the substantia nigra and other brain regions. Both genetic influences and exposure to certain environmental factors, including pesticides, can increase the risk for Parkinson disease. Aging is a major risk factor.

Clinical Features of Parkinson Disease

Parkinson disease has four cardinal signs: tremor at rest, bradykinesia, rigidity, and gait/balance impairment. Resting tremor is characteristically unilateral at onset and remains asymmetric. The tremor typically emerges after few seconds of outstretched posturing of the arms and during ambulation. Bradykinesia is characterized by slowness and gradual lessening of the amplitude of repetitive movements. This feature often is associated with reductions in facial expression and arm swing. Small handwriting (micrographia) is common, and patients may report difficulty with both fine and gross movements. Rigidity, manifesting as increased resistance to movement, is often asymmetric and may occur on the same side as tremor. It may be “cogwheel” with intermittent release of the rigidity with passive movement, resulting in a jerking or ratcheting quality of movement. As many as 30% of patients with Parkinson disease have a tremor-free akinetic rigid syndrome at presentation. Gait disturbance manifests as a slow, narrow-based, and shuffling gait with associated reduced arm swings, stooped posture, and imbalance when turning. As the disease progresses, severe freezing of gait and postural instability are noted. In contrast, cerebellar ataxic gait is characterized by a wide base, frequent truncal swaying and veering, and impaired tandem walking in a straight line. Additional cerebellar signs, such as nystagmus, scanning speech, and extremity dysmetria, also may be seen in cerebellar disorders. Early prominent postural instability with frequent falls suggests a Parkinson-plus condition.

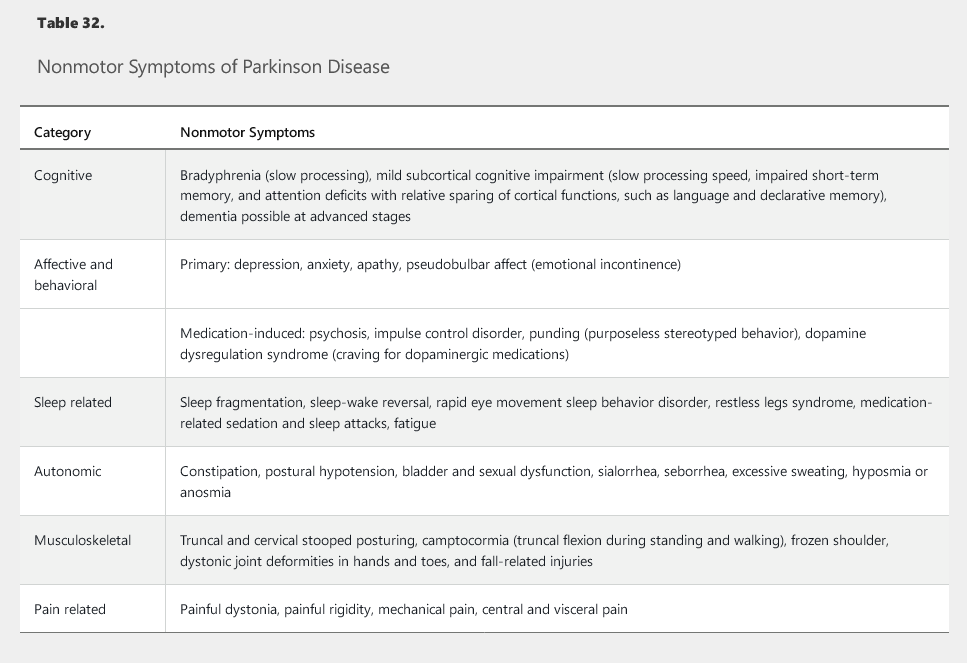

Parkinson disease also is associated with various nonmotor symptoms, ranging from autonomic dysfunction to problems with sleep, mood, and cognition (Table 32). Premotor symptoms, including hyposmia (diminished sense of smell), constipation, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder, may precede onset of motor symptoms by years.

Cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease is not uncommon and initially involves mild subcortical deficits, especially in processing speed, short-term memory, and attention domains. Cortical functions, such as language and declarative memory, are relatively spared. As many as a third of patients may develop dementia in the later stages of Parkinson disease, but early cognitive impairment is a red flag pointing to other diagnoses, such as dementia with Lewy bodies (see Cognitive Impairment).

Diagnosis of Parkinson Disease

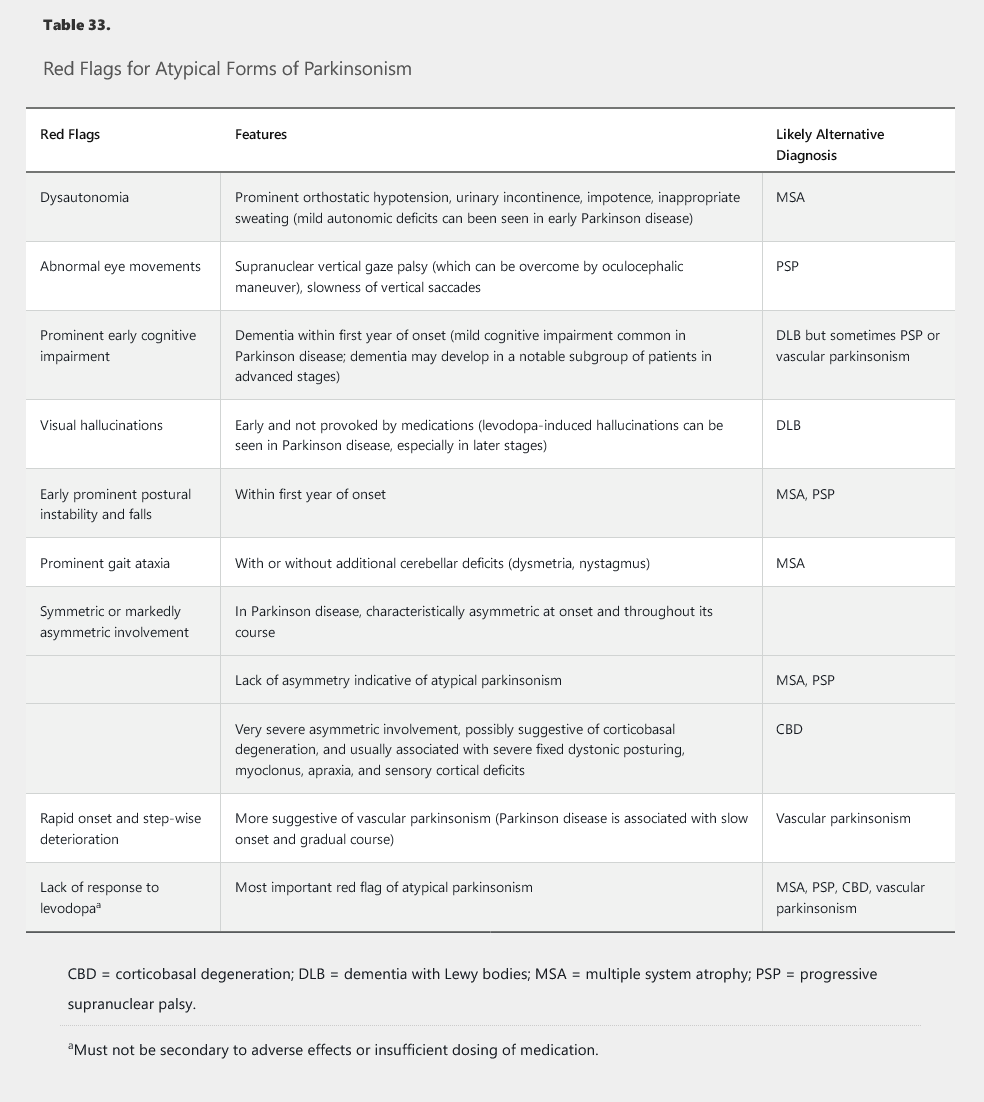

The diagnosis of Parkinson disease requires the presence of bradykinesia and at least one other cardinal feature and the absence of red flags for atypical forms of parkinsonism (Table 33). Brain imaging is recommended to rule out vascular disease and hydrocephalus. A dopamine transporter scan, such as a single-photon emission CT scan of the brain using ioflupane-123 ligand, can be used as a confirmatory test. Its use, however, should be limited to select patients in whom the differentiation between Parkinson disease and essential tremor or drug-induced parkinsonism is not possible on clinical grounds. The test cannot distinguish between Parkinson disease and Parkinson-plus conditions. A therapeutic trial of levodopa also can help when the diagnosis is in question; patients with Parkinson disease usually respond well, but other disorders rarely improve with levodopa.

Depression and Fall Screening

All patients with Parkinson disease should be screened for depression and be assessed for fall risk. Depression and anxiety are common nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson disease and can be detected by using common clinical mood and anxiety scales. Treatments include psychotherapy, antidepressants (excluding antipsychotic agents), and dopaminergic medications (when mood symptoms correlate with motor symptoms). Depression should be distinguished from apathy, a state of reduced motivation and goal-directed behavior that is not associated with emotional distress.

Falls in Parkinson disease may be related to postural imbalance, insufficient control of motor symptoms, or orthostatic hypotension. Detection of risk factors for falling and implementation of a multidisciplinary approach—including medications, therapy, supportive devices, and education—can reduce morbidity and costs related to falls. Postural stability can be best assessed by the pull test, in which an examiner throws the patient off balance by pulling backward on the shoulders. A positive test, characterized by toppling into examiner's arms or taking more than two corrective steps, is the most reliable predictor of a risk of backward falls.

Treatment of Parkinson Disease

Currently, no medication with established efficacy is available to slow the progression of Parkinson disease. Rigorous daily exercise can improve the quality of gait and balance and also may provide disease-modifying benefits.

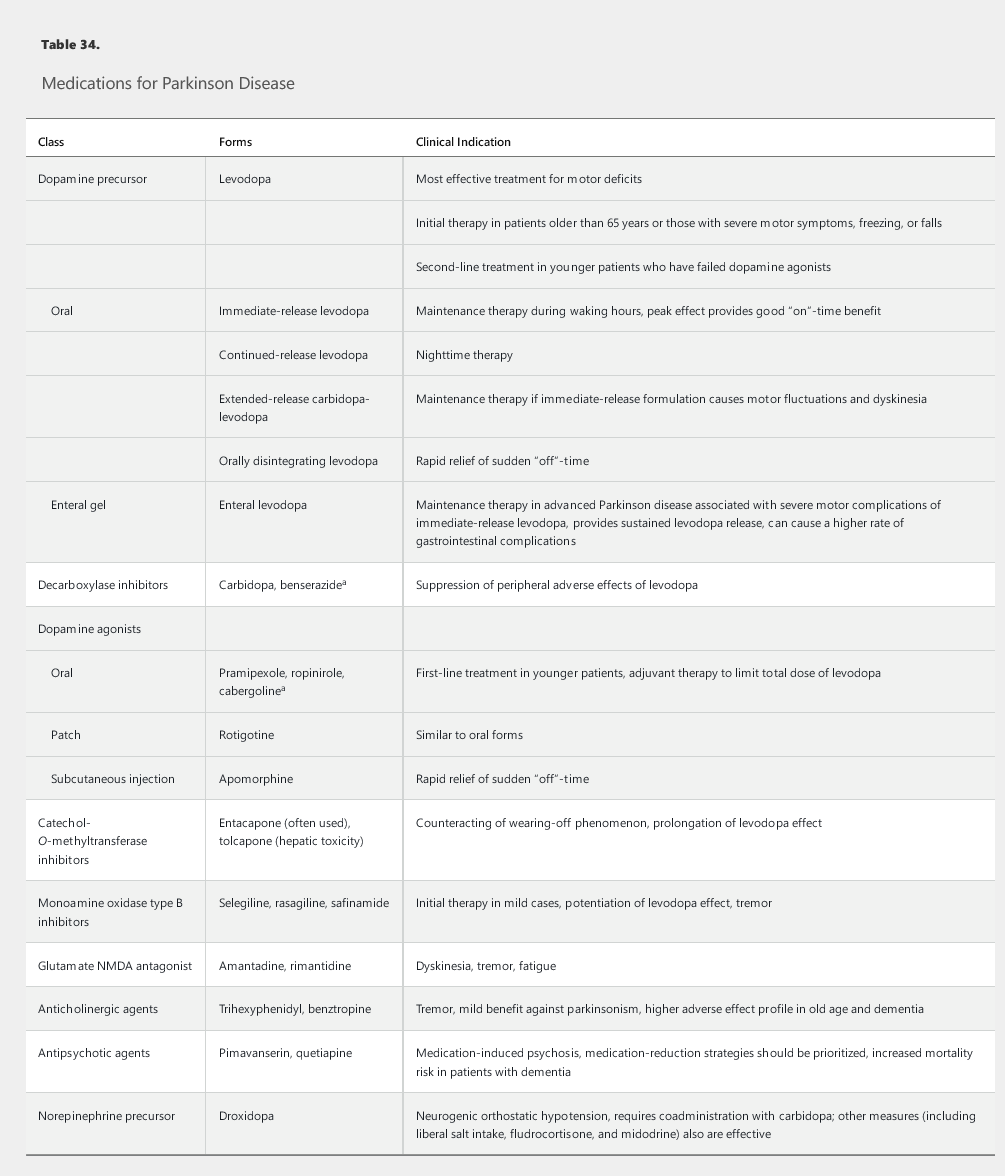

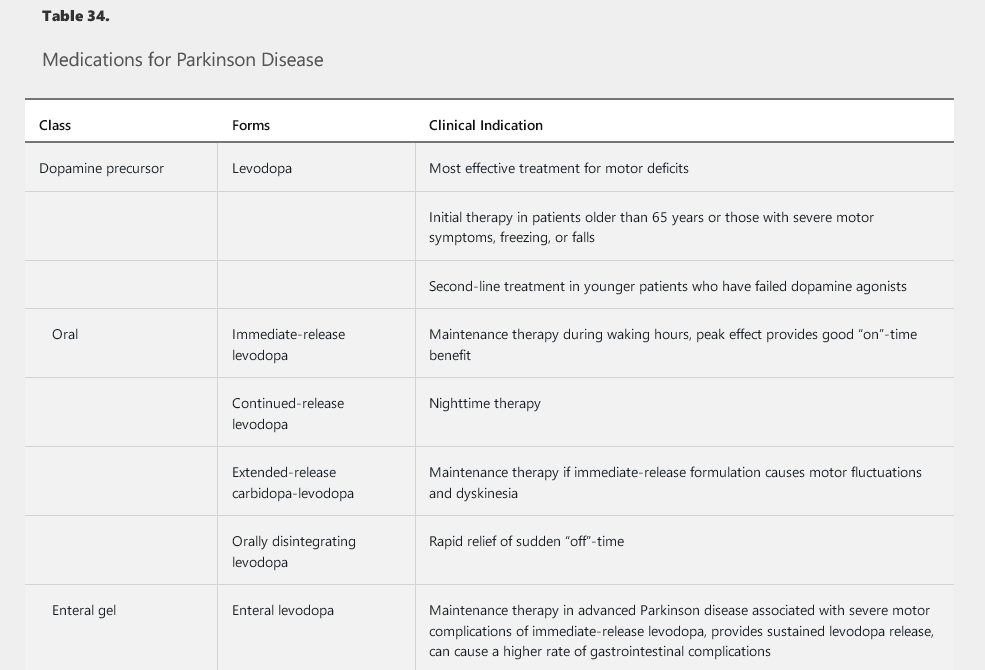

Symptomatic treatments include medications (Table 34), surgical therapy, and supportive measures. Dopaminergic medications (various formulations of the dopamine precursor levodopa, pramipexole, ropinirole, and rotigotine) are the mainstay in the treatment of motor symptoms. Several other medications can supplement the dopaminergic agents and help reduce the medication-induced complications that may emerge over time as Parkinson disease progresses (see Table 34).

Dopamine agonists, such as pramipexole and ropinirole, are the preferred initial first-line dopaminergic medications in patients younger than 65 years and may be used with levodopa as an adjunct treatment at any point in the disease course. Many experts encourage the use of dopamine agonists in younger patients to decrease long-term exposure to levodopa and to delay the onset of levodopa-related complications. Patients taking dopamine agonists should be warned about impulse control disorder, which manifests as a tendency to engage in out-of-character impulsive behaviors, such as excessive gambling, overspending, and hypersexuality. Other adverse effects include sleep attacks, dependent edema, nausea, hallucinations, and confusion.

Eventually, all patients with Parkinson disease will require levodopa. The drug should be started as initial therapy in older patients and as replacement or additional therapy in younger patients with insufficient response to dopamine agonists. Carbidopa, a peripheral decarboxylase inhibitor, blocks the adverse effects of levodopa outside the brain and is used in combination with levodopa. Motor fluctuations, such as the “wearing-off” phenomenon (loss of the beneficial effect of the medication before the next dose is administered) and medication-induced dyskinesia (involuntary choreic movements), are common problems with levodopa. These complications emerge in as many as 50% of patients treated for more than 5 years with levodopa and may reflect disease progression rather than duration of exposure to levodopa.

Several formulations of levodopa are commercially available, including oral immediate-release, extended-release, and rapidly disintegrating formulations; an enteral gel infusion also has recently become available (see Table 34). The immediate-release formulations of levodopa have a rapid peak dose effect that many patients find helpful. The newer extended-release formulations may provide a more sustained control of symptoms throughout the day, which can prove beneficial by reducing any wearing off between doses. Wearing off also can be lessened by frequent dosing of levodopa and by the addition of dopamine agonists, catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors, or monamine oxidase B inhibitors. Amantadine can be added to the treatment regimen to prevent dyskinesia. Anticholinergic medications also can be added to provide additional benefit in patients with prominent tremor or dystonia; adverse events, such as urinary retention, constipation, tachycardia, and memory impairment, are limiting factors, especially in older patients with dementia. Finally, droxidopa, a norepinephrine precursor, can improve neurogenic orthostatic hypotension.

"A 66-year-old man with a known history of Parkinson disease complains of very painful involuntary contractions affecting the toes of both feet. The contractions occur in the morning, soon after he wakes up, and occasionally wake him from sleep. The episodes last about 15-20 minutes."

Motor fluctuations occur as episodes between levodopa doses when the drug "wears off" and patients develop symptoms of their underlying PD. These symptoms can occur after awakening, during a specific part of the day, or in the middle of the night. Dystonia is a common painful symptom that can occur spontaneously in the early disease stages or as part of motor fluctuations. Morning dystonia of the feet usually occurs due to low levels of levodopa during sleep. Akathisia (motor restlessness) can also result from levodopa withdrawal and usually occurs at night.

Given that this patient's symptoms are worse in the middle of the night and morning hours, it is reasonable to start a longer-acting carbidopa/levodopa at night to ensure steadier levels. Other considerations include taking levodopa or a dopamine agonist at night or first thing in the morning before arising.

Medication-induced psychosis, especially visual hallucinations, also can occur with use of dopaminergic medications. Treatment strategies include addressing any systemic trigger, simplifying the medication regimen (including removal of non-levodopa medications and decreasing the levodopa dosage), and, if needed, using antipsychotic agents. Pimavanserin, a selective serotonin 5-HT2b receptor inverse agonist, is the only FDA-approved medication for Parkinson psychosis; quetiapine and clozapine also are often used as less expensive, albeit off-label, options.

In patients with severe motor complications, enteral infusion of carbidopa-levodopa gel through a jejunal tube with a portable pump can provide more sustained levodopa release and reduce motor complications. High rates of gastrointestinal and tube-related complications are limiting factors.

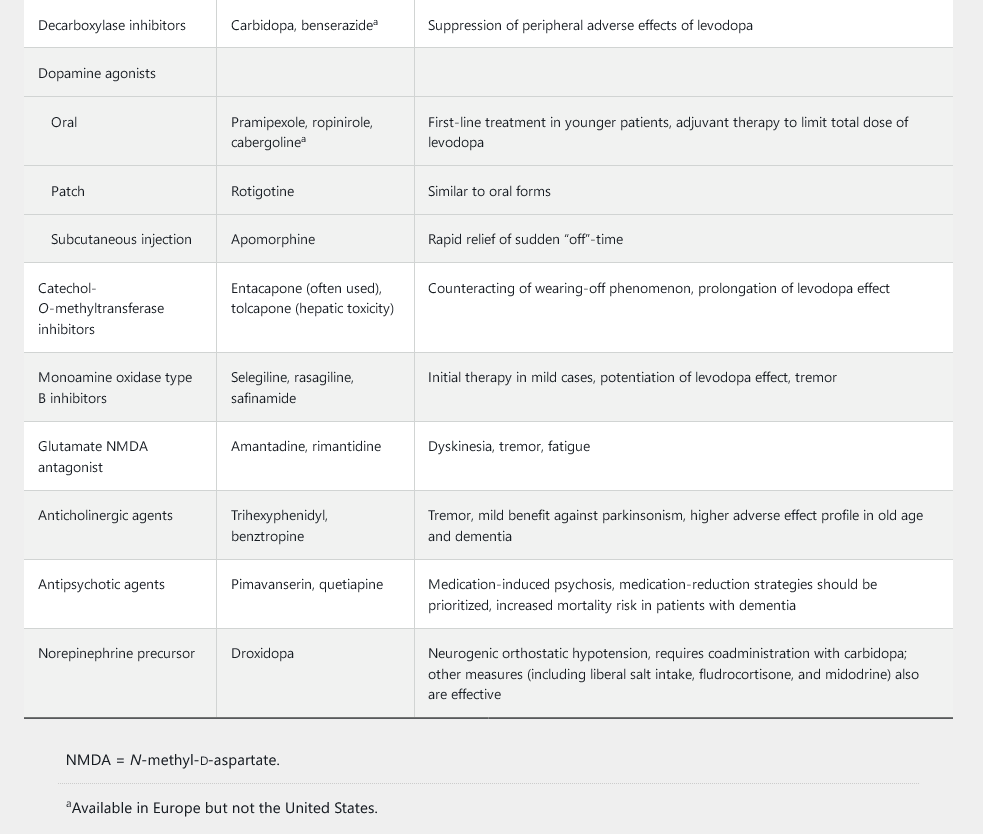

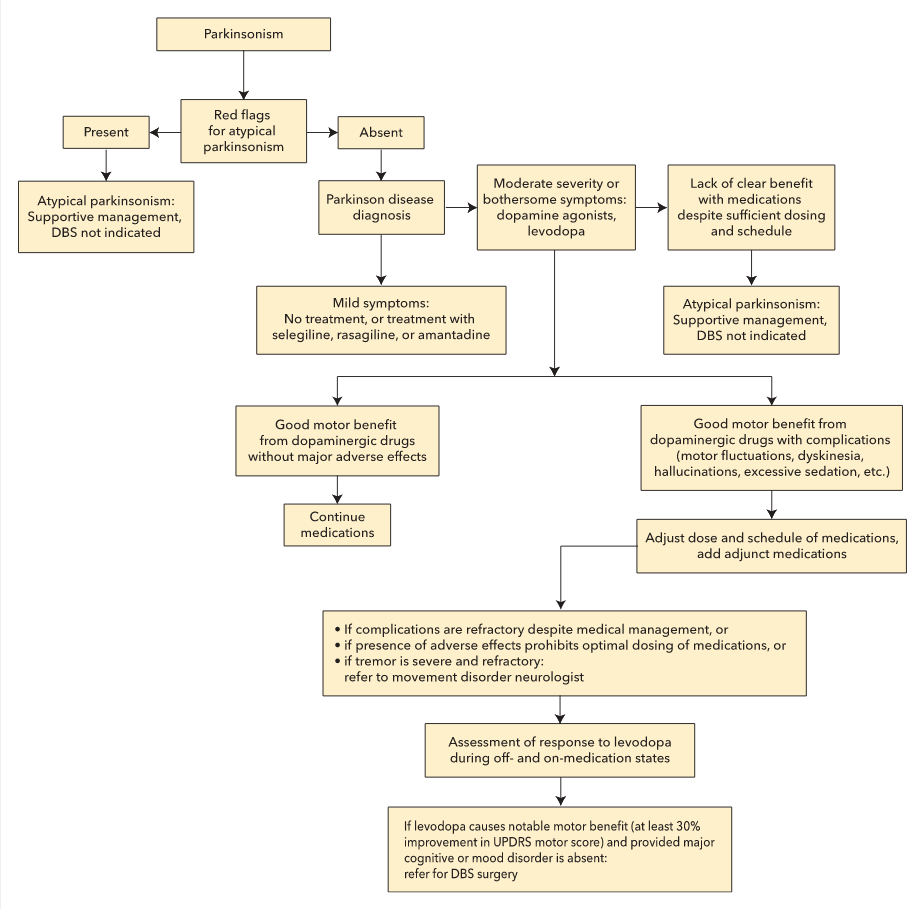

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a surgical therapy that involves the delivery of electrical stimulation to key brain targets, such as the subthalamic nucleus and the globus pallidus interna. The stimulation disrupts the abnormal neurophysiologic activity within the basal ganglia and simulates a patient's response to medications. This mode of treatment is indicated for patients who continue to benefit from levodopa but experience severe motor fluctuations or have a refractory tremor. An algorithm for selection of appropriate candidates for DBS surgery is shown in Figure 21. Given the evidence of improved quality of life after early implementation of DBS, the FDA has expanded the indication for this procedure to patients with Parkinson disease of 4 years' duration who experience early motor fluctuations.

Deep brain stimulation enables a persistent motor benefit and reduction of the total levodopa dosage, which would diminish the levodopa-induced adverse effects, including dyskinesia, nausea, and orthostatic hypotension.

Algorithm for evaluation of candidacy for deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease. DBS = deep brain stimulation; UPDRS = Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale.

Algorithm for evaluation of candidacy for deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease. DBS = deep brain stimulation; UPDRS = Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale.

Parkinson-Plus Syndromes

Parkinson-plus syndromes typically present with a combination of parkinsonism and additional features that are atypical for idiopathic Parkinson disease. These conditions often are more rapidly progressive than Parkinson disease and less responsive to standard therapies, particularly levodopa. The primary syndromes include progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy (formerly Shy-Drager syndrome, acquired olivopontocerebellar atrophy, and striatonigral degeneration), and corticobasal degeneration. Patients with progressive supranuclear palsy have parkinsonism, impairment in both ocular range of movement and saccades (very fast jumps from one eye position to another, particularly in the vertical direction), facial dystonia, axial rigidity, and prominent postural instability with early falls. Multiple system atrophy presents with a combination of parkinsonism, ataxia, and severe dysautonomia and also is associated with early falls. Corticobasal degeneration often presents with markedly asymmetric parkinsonism and frequently is associated with dystonia, myoclonus, cortical sensory deficits, cognitive deficits, and apraxia (impaired motor planning).

Drug-Induced Parkinsonism

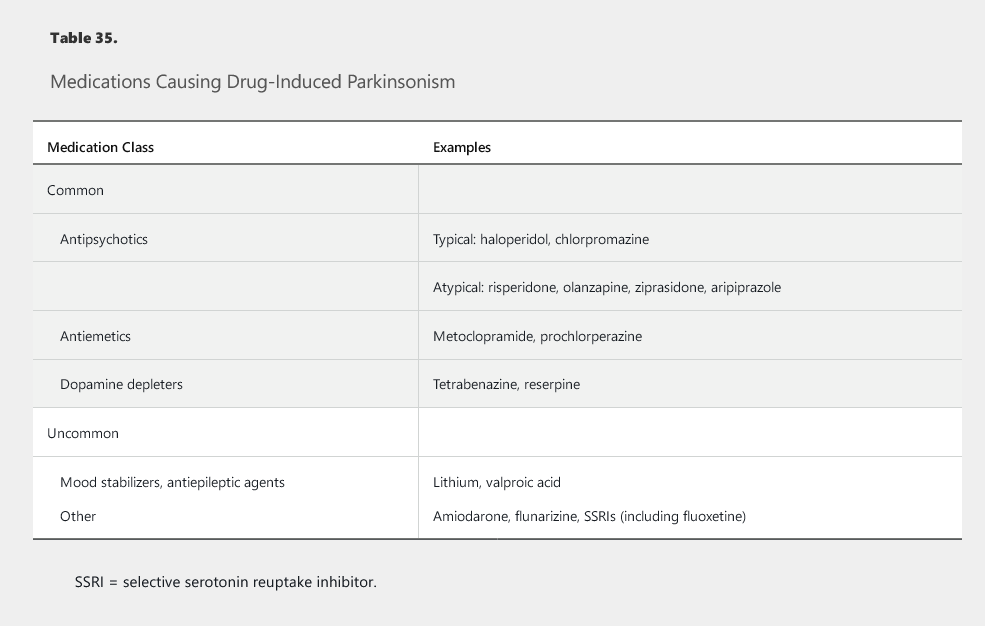

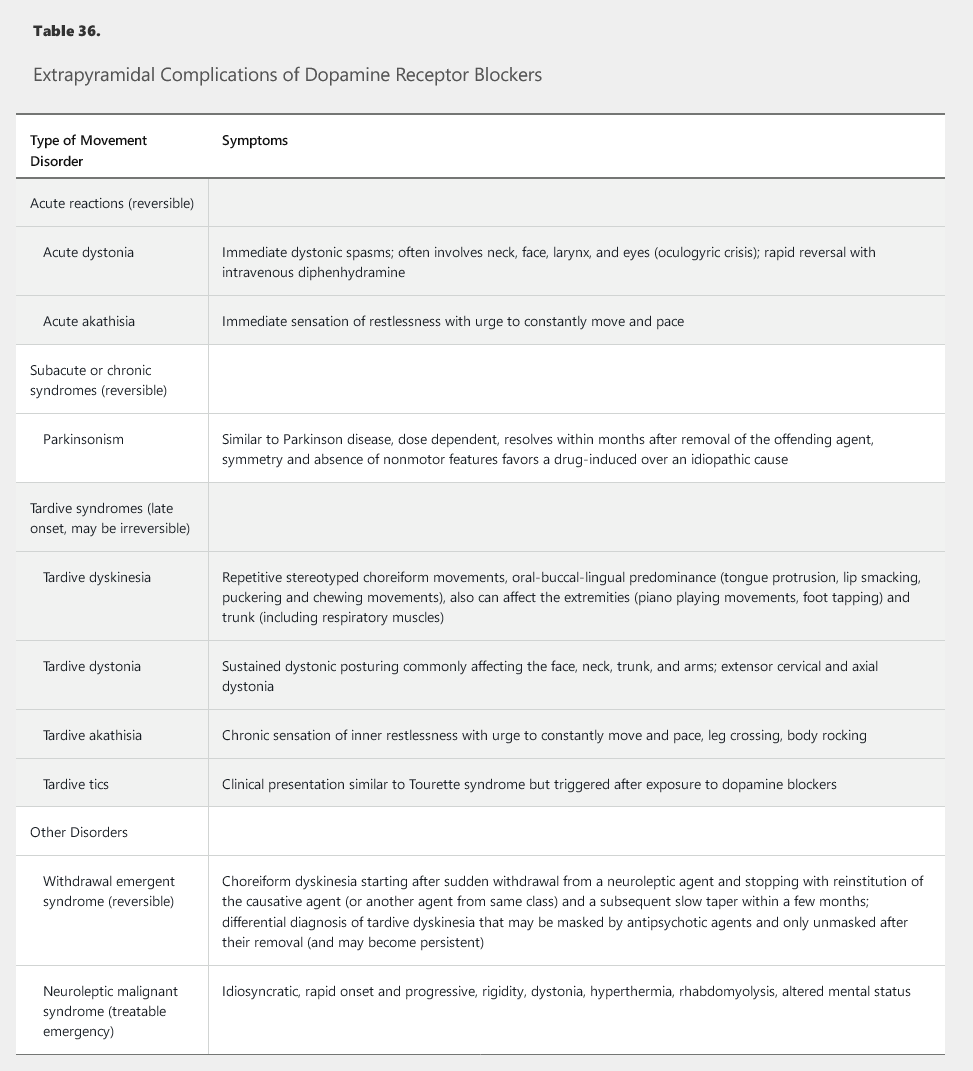

A number of drugs, especially dopamine receptor–blocking antipsychotic agents, can cause parkinsonism (Table 35). Drug-induced parkinsonism is symmetric, lacks nonmotor features, and is reversible after removal of the causative agent. Several other extrapyramidal complications of dopamine-receptor blockers have also been described (Table 36).

Hyperkinetic Movement Disorders

Essential Tremor

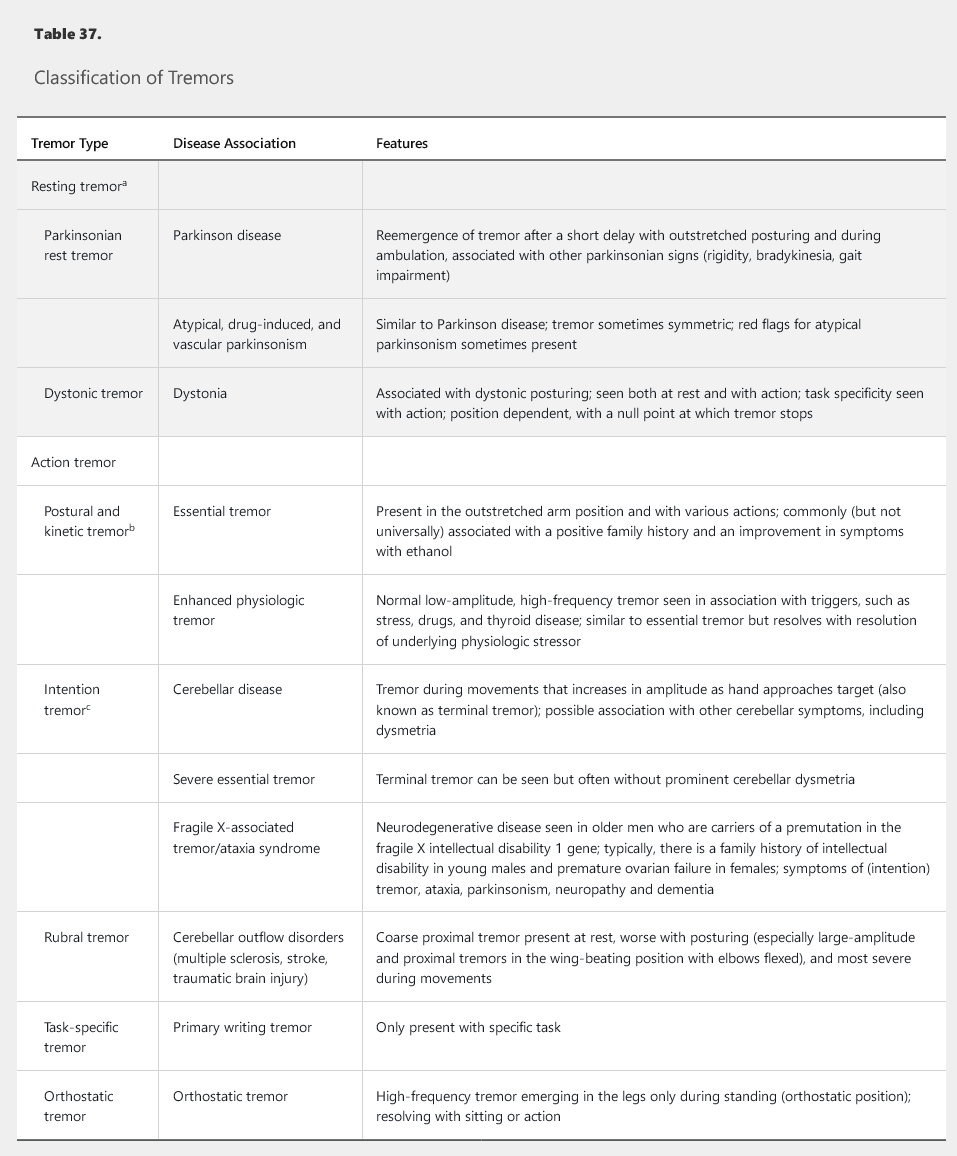

Tremor is an oscillatory movement of a body part that is classified on the basis of its presence at rest or with action (Table 37). Essential tremor is the most common movement disorder and often presents with a bilateral upper extremity postural and action tremor. This type of tremor also can involve the voice, head, or legs. Common features include a positive family history (50% of patients), slow progression, and onset at either adolescence or middle age. The tremor may be alleviated by alcohol and may be aggravated by stress, illness, fatigue, or the use of caffeine or other stimulants. A minority of affected patients experience substantial progression, leading to marked disability.

- a. Tremor present with the affected extremity resting unsupported.

- b. Postural tremor is present with the arm in an outstretched position, and kinetic tremor is present during reaching, writing, and other movements.

- c. Intention tremor is a specific subtype of kinetic tremor that becomes very prominent near target, exhibiting a crescendo of increased severity at the terminal section of the movement path.

The differential diagnosis includes enhanced physiologic tremor, which is a low-amplitude tremor that is unnoticeable in most people but may become prominent because of physical and psychological stressors, medications, thyroid disease, or caffeine. Assessment of any form of action tremor should include thyroid function studies and review of medications (Table 38). Patients younger than 40 years should undergo screening for Wilson disease with serum ceruloplasmin and 24-hour urine copper measurements, and slit-lamp examination for Kayser-Fleischer rings should be considered. Other rare causes of action tremor include dystonic tremor, rubral tremor, and fragile X–associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (see Table 37).

The treatment of essential tremor is symptomatic. Weighted utensils and wrist weights can help reduce tremor amplitude during feeding. The most effective pharmacologic treatments for essential tremor are propranolol, primidone, and topiramate. Additional second-line options include atenolol, sotalol, clonazepam, gabapentin, and nimodipine. Botulinum toxin injection can help with some tremors, especially those involving the neck and voice, but its benefit for limb tremor is limited by local weakness. Medication-refractory tremor can be effectively treated by targeting the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus with DBS or thalamotomy.

Dystonia

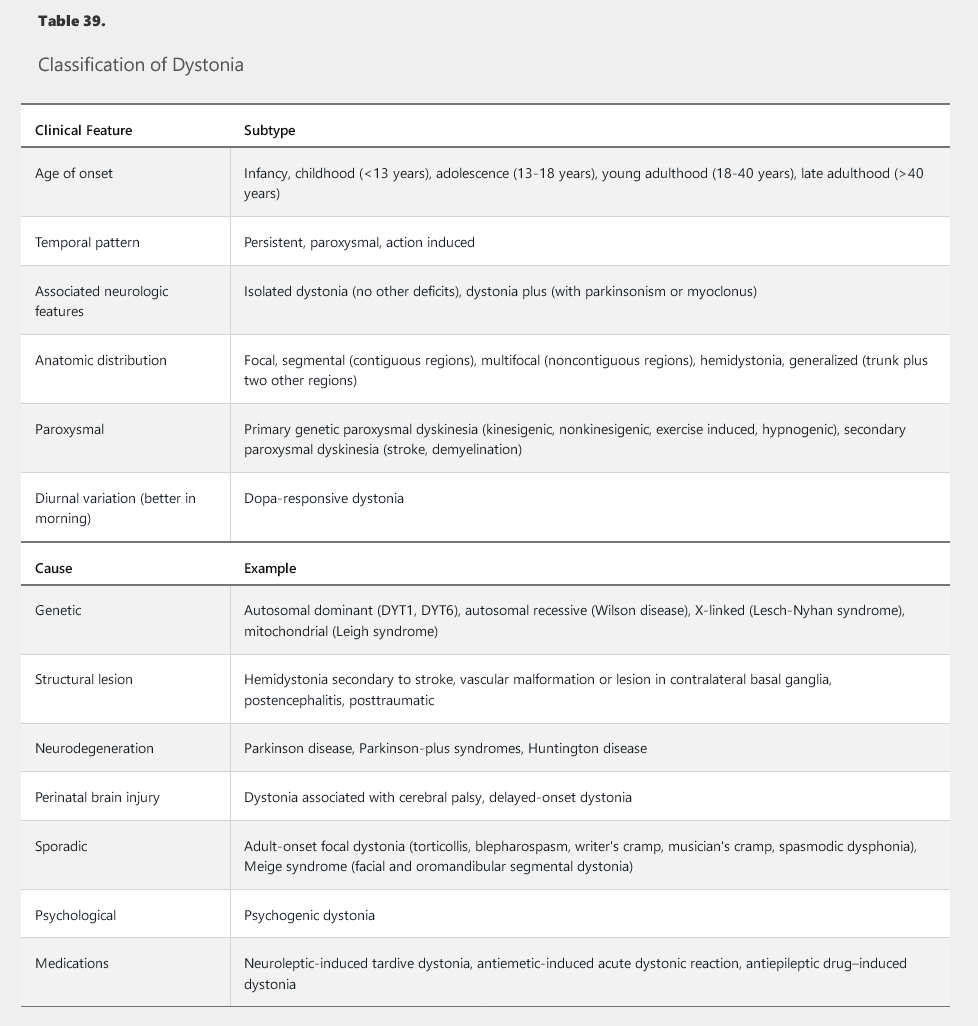

Dystonia involves sustained or intermittent muscle contractions leading to stereotyped and directional twisting and posturing movements of various body parts. Dystonias are classified according to age of onset, body distribution, temporal pattern, associated features, and cause (Table 39). Generalized dystonias involve multiple body parts, including the trunk, whereas focal and segmental dystonias have a more restricted distribution and usually spare the lower extremities. Hemidystonia is limited to one side of the body. Generalized dystonias often start at a young age (<25 years) and have inherited, metabolic, or vascular causes. The most common type of generalized dystonia involves mutation in the dystonia 1 gene (DYT1). Patients with primary generalized dystonia should be challenged by a short trial of levodopa to screen for dopa-responsive dystonia, a rare but treatable cause of generalized dystonia. Young adults with progressive dystonia should be screened for Wilson disease, especially in the presence of other associated findings (such as tremor and parkinsonism).

Focal adult-onset dystonias include cervical dystonia (spasmodic torticollis), eyelid dystonia (blepharospasm), vocal cord spasmodic dysphonia, and task-specific hand dystonia (writer's cramp). Cervical dystonia often involves involuntary deviation of the head from midline, an irregular head tremor that lessens with positional changes (null point), and transient improvement of movements by specific sensory tricks (such as gently touching the face with the hand). The null point is the position at which the trajectories of the forces caused by dystonic coactivation of agonist and antagonist muscles neutralize each other, which leads to resolution of the tremor. Treatment includes anticholinergic agents, benzodiazepines, baclofen, and levodopa. Injection with botulinum toxin targeting the most active muscles in focal dystonia also is beneficial. In genetic or idiopathic dystonia, DBS of the globus pallidus interna can markedly improve symptoms. The benefit of DBS is more variable in secondary dystonia with the exception of tardive dystonia, which responds well.

Choreiform Disorders and Huntington Disease

Chorea manifests as random, nonrepetitive, flowing dance-like movements and can be caused by medications, endocrine derangement, streptococcal infection (as in Sydenham chorea in rheumatic fever), autoimmune disease, pregnancy, and neurodegenerative disorders involving the basal ganglia (Table 40). The most common neurodegenerative cause of generalized chorea is Huntington disease, which involves symptoms of progressive parkinsonism, gait impairment, impulsiveness, psychiatric disease, and dementia. Substance abuse also has been associated with Huntington disease. An autosomal dominant condition, this disorder is caused by a trinucleotide repeat expansion in the huntingtin gene. Age of onset has a reverse correlation with length of repeat expansion and may be younger with paternal transmission (anticipation phenomenon). Huntington disease is invariably fatal. Symptomatic treatments of chorea include the dopamine depleters tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine, antipsychotic agents, clonazepam, and antiepileptic drugs.

Myoclonus

Myoclonus is a brief, shock-like, jerky movement that can be physiologic (hiccups, hypnic jerks at sleep onset) or pathologic (caused by medications, toxins, or systemic or central disease) (Table 41). Myoclonus can originate from various parts of the nervous system, including the cortex, subcortical structures, the spine, or peripheral nerves. Cortical myoclonus is often epileptic. Negative myoclonus is caused by sudden loss of muscle tone, as seen in asterixis and in the legs after hypoxia (Lance-Adams syndrome). Treatment of myoclonus includes addressing the underlying systemic or toxic cause and administering antimyoclonic agents, such as clonazepam, valproic acid, levetiracetam, zonisamide, or topiramate.

Tic Disorders and Tourette Syndrome

Tics are stereotyped, rapid movements interrupting the flow of normal movements. Tics may provide transient relief in response to premonitory unconformable sensations and are at least partially suppressible. Tics usually start during childhood and subside during adulthood, but they may persist in a minority of those affected.

Tourette syndrome is characterized by childhood-onset motor and phonic tics with a duration of at least 1 year. Phonic tics include vocalizations and, less commonly, echolalia (repetition of others' words) and coprolalia (utterance of obscenities). Tic severity may range from minimal to very disruptive. Tourette syndrome is considered a network disease in which basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex interactions are dysregulated. Common comorbidities include attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and mood disorders. Diagnosis is clinical. Treatment options include reassurance (often appropriate in mild disease), cognitive behavioral therapy (including tic diversion techniques), and addressing psychiatric comorbidities. Anti-tic medications are indicated when tics interfere with daily functioning, education, or work. First-line treatments are clonidine, guanfacine, topiramate, levetiracetam, and tetrabenazine. Antipsychotic agents (aripiprazole, pimozide, ziprasidone, risperidone, and haloperidol) can help in the treatment of refractory tics, but the risk of tardive dyskinesia should be considered in adults. Botulinum toxin may be useful for focal tics and severe refractory disease; DBS may also be beneficial in severe disease.

Restless Legs Syndrome and Sleep-Related Movement Disorders

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a common movement disorder characterized by an urge to move the legs. Patients report an uncomfortable sensation that is worse at rest and at night and is transiently relieved by movement. Patients with RLS should be screened for iron deficiency because iron supplementation in the presence of low-normal ferritin levels (15-75 ng/mL [15-75 μg/L]) may resolve the symptoms. Other risk factors for RLS include uremia, sleep apnea, pregnancy, and certain medications (including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antipsychotic agents, and stimulant drugs). Nonpharmacological measures include improvement of sleep hygiene, exercise, and the use of a vibrational device. First-line pharmacologic treatments include dopamine agonists (especially pramipexole and the rotigotine patch). Additional options include ropinirole, gabapentin, pregabalin, levodopa, and opioid agonists (prolonged release oxycodone-naloxone and methadone). Chronic use of dopamine agonists, however effective, may lead to either augmentation (that is, symptoms start earlier in the day) or rebound (that is, symptoms return with greater severity after the medication wears off). Use of long-acting formulations can lessen both of these complications. Gabapentin enacarbil, an α2 δ calcium channel ligand, is a slow-release prodrug of gabapentin that is also FDA approved for the treatment of RLS. Opioids are typically restricted to patients with severe symptoms recalcitrant to other therapies. Physicians prescribing opioids for RLS should be adherent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for prescribing opioids. See MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine.

Periodic limb movements of sleep are brief triple flexion movements of the legs that repeat in 20-second cycles during sleep. This disorder is very common and can occur independently of or be associated with RLS, sleep-disordered breathing, or narcolepsy. The diagnosis is made by using polysomnography. Treatment of this disorder is only required if it causes marked sleep fragmentation.

REM sleep behavior disorder is caused by loss of normal paralysis during the REM phase of sleep, leading to dream-enactment behavior. Patients with this condition tend to shout, kick, punch, and jump while dreaming. Diagnosis is based on either the report of a bed partner or polysomnography. The main differential diagnosis is nocturnal epilepsy. REM sleep behavior disorder responds well to clonazepam and melatonin. It is a strong predictor of future development of synuclein-related neurodegeneration, such as Parkinson disease, multiple system atrophy, or dementia with Lewy bodies.

Other Drug-Induced Movements

Tardive Dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesia is an extrapyramidal complication of dopamine receptor–blocking medications (see Table 36). It is associated with characteristic choreiform and dystonic craniofacial movements, which often involve other body parts, such as the neck and trunk. Treatment involves removal of the offending medication. Symptoms of dyskinesia, however, can take months to resolve or become permanent. Longer duration and higher doses of medication exposure, older age, and female gender increase the risk of irreversibility. Risk is highest with typical antipsychotic agents, but many atypical antipsychotic and antiemetic agents also can cause tardive dyskinesia. All patients receiving these agents must be warned about the risk of this complication. Recently, valbenazine, a monoamine depleter, was the first medication to receive FDA approval for treatment of tardive dyskinesia. Other pharmacologic therapies include tetrabenazine, amantadine, clonazepam, and anticholinergic agents. In severe cases, DBS of the globus pallidus may be effective, although it lacks FDA approval for this indication.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is an acute life-threatening disorder caused by an idiosyncratic reaction to therapeutic doses of dopamine-blocking agents. Its pathophysiology involves a sudden decrease in dopamine D2 receptor activity. Patients present with fever, rhabdomyolysis, altered mental status, rigidity, and dystonia. The creatine kinase level often is remarkably elevated. The most effective treatment is removal of the offending agent and supportive management. Treatment options include dopamine agonists and the muscle relaxant dantrolene, although there is weak evidence supporting their effectiveness. Mortality may be as high as 10%. Patients who have dementia with Lewy bodies are particularly susceptible to neuroleptic malignant syndrome. A similar syndrome can be triggered by rapid withdrawal of dopaminergic medication in patients with Parkinson disease, including when medications are stopped in the hospital before surgery. See MKSAP 18 Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine for more information about neuroleptic malignant syndrome.